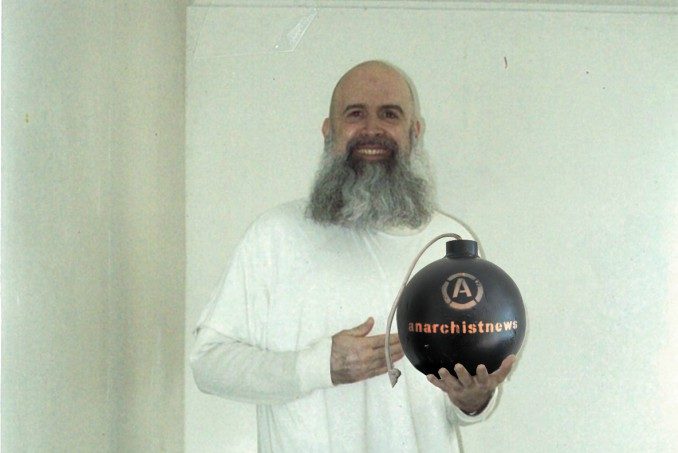

In our latest interview for the June 11th International Day of Solidarity with Marius Mason & All Long-Term Anarchist Prisoners, we spoke with anarchist prisoner Sean Swain.

Sean is an anarchist prison rebel held captive since 1991 for the self-defense killing of a court official’s relative. In fall of 2012, Sean was blamed for widespread sabotage at Mansfield Correctional as part of the Army of the 12 Monkeys. He continues to organize, write, and contribute weekly segments to The Final Straw radio program.

We talk about Sean’s history and experiences in prison, outside support as essential to breaking the control prison imposes upon its captives, the Army of the 12 Monkeys’ campaign of diffuse sabotage at Mansfield Correctional, Sean’s critique of and participation in hunger strikes, the upcoming republishing of two of Sean’s books, prisoner self-organization, the Palestinian hunger strike, and making every day June 11th.

JUNE 11TH: Can you start by telling us about yourself and your experiences with prison?

SEAN SWAIN: I grew up just north of Detroit in the ‘burbs. I was in Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts; probably nobody was more obedient with the program than I was. I went into the army and spent two years miserable and traumatized, and not long after I got out, the ex-boyfriend of the woman I was living with at the time kicked in the door. I stabbed him and killed him, and he was the nephew of the clerk of courts. What actually happened doesn’t really matter, because if you ever kill anybody more equal than you, you go to prison. I’ve been locked up since 1991. The more I protest that I didn’t commit a crime, the longer those bastards keep me held hostage. Go figure.

I had a writing scholarship before I came to prison. Because I was a writer, I was writing for prison reform groups and other reformist stuff. That kind of annoyed prison officials. I had a psychologist at Toledo once tell me that the most annoying thing to people who run prisons is somebody who is articulate; they hate that. As a result, it created this situation where prison officials hate me more as time goes on. You would think they’d just let me go. That’s what I would do.

J11: Can you speak to the importance of prisoner support as part of the anarchist project and specifically to the necessity of long-term prisoner support?

S: I hope I can give you a sense of what it means to be the beneficiary of prisoner support. It’s not about the funds, which are certainly nice, and it’s not about the visits, which are also nice—it’s about a sense of identity, too. It’s about validation. The prison complex does what it can to define each of us as offenders and inmates and criminals; they impose identities on us. It’s much easier to reject that kind of pathology when there’s a base of support—when there’s a group of people who know you and define you differently. Because of those relationships and those connections, I’ve spent most of my prison time not in prison. What I mean is: I’m real to people on the other side of the fence. I’m present in their lives on that side of the fence. That makes the prison fence somewhat irrelevant.

I’m reminded of Henry David Thoreau, who wrote about how he marveled at his captors’ blunders when they confined his body in the jail, but let his thoughts slip out through the bars right behind them when they left for the day. For me, prisoner support isn’t “prisoner support;” it’s more like mind and identity reclamation. I exist on the other side of the fence, and I have meaning out there, which gives me meaning and purpose for getting up in the morning. I care about those people and they care about me; they make it possible for me to participate in changing the world. These people have reduced prison and captivity to a question of geography. I happen to be on this side of the fence, which is really meaningless, since my physical body isn’t what makes me dangerous to our common enemy. In many important respects, my physical captivity has become of practical irrelevance. People out there have made that true.

J11: Earlier this year you went on a successful hunger strike for more than fifty days. Could you tell us more about that?

S: I have to begin with the disclaimer that I have consistently said hunger strikes are stupid; they are. They rarely work, because prison officials—going all the way back to Margaret Thatcher with the IRA hunger strikers in something like 1980—they’ll either let you die (if they can get away with it), or they’ll torture you until you eat if they can’t get away with killing you. They’re ruthless sociopaths. You can’t really appeal to the consciences of ruthless sociopaths because they don’t have any.

This hunger strike was a partial success because I got my communication mediums restored after fifty days without food. That wasn’t because of their concern for my health or any other such nonsense; it was because of outside forces that came into play. There’s a website (blastblog.noblogs.org) where Ohio prison officials’ home addresses were posted; it might still be there. They decided I’m somehow responsible for that. I run the internet with my tin-foil hat from my prison cell, I guess. Anyway, after 32 days on hunger strike and no negotiations at all, I handed them the obituary I had written. That said, essentially: Swain’s dead. The prison director killed him, and they’re denying it because they want to get security around their homes before they announce that Swain’s dead.

Because Blast! Blog was out there, that scared them. They realized that if that got posted online, people might actually get mad enough to do something. The deputy warden came in around 6:30 one morning and he was pissed. He said he was getting calls from exotic area codes giving him death threats. At the very least, fifty days of that nonsense was annoying enough for the state to make some concessions, so I have my communications restored. They never should’ve been suspended in the first place.

I really hate hunger strikes because, in a sane world, we wouldn’t threaten to hurt ourselves to get what we deserve. We’d hurt the fascists who have it coming. To me it’s a lot more psychologically healthy to punch your enemy in the face than it is to refuse food. The problem is, they neutralize you before you get your hands on the ones who’ve really got it coming: senators, judges, corporate executives, and the NSA guy who’s recording this. Those people.

J11: For years you’ve contributed regular segments to The Final Straw (an anarchist radio show). What has this meant to you, and what do you hope it could mean to others and to the wider struggle?

S: It’s strange, because when you’re doing the segments—I’m calling on the phone, just like when I’m talking to you. I don’t necessarily get a whole lot of feedback. It’s almost like putting a message in a bottle and flinging it into the ocean; you don’t know where it ends up. What’s funny is that it seems to have an impact on the way the prison administration deals with me. I get a lot of feedback from listeners, but I get a good sense of the impact it has on the people who are holding me captive. That’s kind of cool. I’m hoping it impacts how people view—not just prisoners, but the relationship that people out there can have with prisoners (or should have with prisoners): that there’s something potentially of value in interacting with people who are in here.

J11: We’re looking forward to the publication of two of your books (How Emma Saved the World and Last Act of the Circus Animals) in the coming months. Can you tell us more about those stories?

S: Last Act of the Circus Animals was co-written with Travis Washington, who is another prisoner. It stemmed from some conversations we had. He actually started it; I was really jealous because he hadn’t really done any writing before that, and I was writing all kinds of stuff. He came up with this excellent metaphor of animals who are in the circus, in cages, and they start talking to each other. There’s one panther in particular who starts raising the consciousness of the other animals as to the real nature of the circus. He came up with what’s actually the first chapter of Last Act of the Circus Animals. I read that, and that’s all he was going to publish, and I said: No, this is just the beginning. He didn’t have any confidence in his ability to write what I was proposing, so he suggested that we write it together. I took over the writing aspect of it and he and I worked on the remainder of the story … it’s kind of a metaphor.

Anthony Rayson was the first publisher/distributor who put that out in 2007, probably over the course of about two and a half years. It ended up everywhere. I was getting mail from Russia; people in Russia had read Last Act of the Circus Animals. It was reviewed in the UK in a publication. In every prison I’ve been to, somebody has walked up to me at some point and said: Are you Swain? Are you the guy who wrote Last Act of the Circus Animals? They expect me to be taller, I guess. It’s cool that’s it’s everywhere.

With How Emma Saved the World, I deliberately set out to write something as subversive as it could possibly be for young kids. It’s a story about a little girl who jumps on the couch. She’s told not to, so she goes into a whole series of investigations in order to find out why it is that she can’t jump on this couch. She then undertakes to teach the adults what it is that they’re missing.

The idea behind it is that kids know something we’ve forgotten, and what they know is valuable. It’s valid; their experience of the world is valid. It’s very subversive in the sense that Emma, the main character of the story, is self-deferring, so to speak. She defers to her own sense of how things ought to be rather than deferring to those who are supposedly in authority. Hopefully, if that book gets published far and wide, and a lot of kids read it, we’ll have a whole generation of kids who are pulling the fire alarms at their schools in the next few years. That could be really exciting.

J11: What forms of solidarity have been most important to you while you’ve been in prison? What could’ve been done differently, or better?

S: In 2012, when the Army of the 12 Monkeys happened at Mansfield . . . I haven’t talked about that yet. We’ll probably get to that. After that happened, the ODRC engaged in a regimen of torture under the supervision of the FBI. (The FBI was actually involved in some domestic torture stuff: surprise.) In response to that, there were some people who set up a website called Blast! Blog (blastblog.noblogs.org); I’m not sure if it’s still there. The people who’d been involved in that torture regimen had their home addresses posted there, with pictures of their homes and Google Maps features so people could find the quickest routes to get into their houses. . .

Prison officials at the highest levels of the ODRC have told me that they know I’m behind that; they hold me responsible for what’s going on on the internet. Their entire procedure has changed in the last two years. To give an example: in segregation now, they have big-screen TVs. They have programs. They have people who pass out crossword puzzles. Segregation is no longer called segregation; it’s a temporary housing program. On top of all that, it’s now policy that you only go to segregation for violence. Anything that’s nonviolent—you don’t go to seg anymore. There’s no longer long-term segregation. Any kind of long-term punishment happens out in population, in a special housing unit where you get programming.

Everything that was going on when I went to segregation after the 12 Monkeys thing and the whole torture regimen occurred—all of that has changed now. They’ve done a complete about-face, and there’s other reforms, like the whole three-tier system they had before—it was pretty draconian—it created a revolving door so people couldn’t get into lower security . . . That’s all been undone. All of that came about, I believe, as a result of prison officials. First there’s the implied threat of their home addresses getting posted online (I’m sure nobody likes that). On top of that, nobody likes to be seen as a torturer. Nobody wants to be publicly exposed to their kids and their wives and their neighbors and coworkers; nobody wants to be seen that way. In that way, Blast! Blog had a huge effect, I think. It really changed the way the entire Ohio prison system works.

That’s one thing; the website is another. Friends of mine put together SeanSwain.org, and that broadcasts my voice to a much larger audience than just within the prison system. Whether or not anybody’s actually going to the site—I think possibly, maybe, five people keep visiting there—but prison officials don’t know that. Once there’s a web presence, they simply assume that seven billion people on the planet are going there on a regular basis. It has an impact on the way they behave. I think, on top of all that, there’s the added unconscious fear in the back of their minds that it’s going to set a trend—that other people are going to start doing this. Not just the website, but Blast! Blog. Theoretically—I’m not advocating this in a recorded phone call—but things like that have implications beyond the prison complex. You have the same kind of tactics that were employed by Stop Huntington Animal Cruelty. If you start having corporate executives’ home addresses posted all over the place . . . This is something that has much wider implications. Possibly.

J11: You mentioned the Army of the 12 Monkeys, but we haven’t heard a lot about that yet. Can you tell us more of that story?

S: It’s an interesting thing. I was at Mansfield, which is in the middle of Ohio, in the middle of nowhere, and seemingly out of nowhere, there were fliers in every single block. They had some pretty cool graphics on them, and they were listing all the things prisoners can do to disrupt the orderly operation of the prison. In my own thinking, what was really significant about all this is that they didn’t really pose any argument as to why prisoners ought to resist the system or rebel; they just assumed that prisoners would already know. There didn’t seem to be any kind of political line that was promoted, and there didn’t seem to be any real demands. It was just—seemingly—rebellion for its own sake. At first—you have these thousands of fliers everywhere, describing all of these actions that prisoners can do, and at first, nothing happened at all. Almost as if the whole prison compound, the whole population, was wondering if this was some sort of practical joke.

There was a two- or three-day lag, it seemed, and then immediately after that, there were staples in locks all over the prison. Somebody crammed potatoes down the drain in the kitchen and collapsed that. That cost them six figures; they had to dig up the entire floor of the prison and re-lay all the cement, and then three days after they did that, somebody poured dry cement down the pipes and collapsed the plumbing again. So we’re talking about six figures followed by six figures. When you think about all the locks you have in a prison setting, and you start jamming staples in locks, it becomes really disruptive, because nobody can perform the functions of their job. They can’t get into their offices. So you had all of that going on, and then somebody lit the kite box on fire, which is kind of symbolic, because the kite box is the box you put communications in so that prisoners can communicate with staff. So that was lit on fire. The OPI factory (the penal industry factory) was shut down continually by disruption and sabotage of the machinery, so they were getting no production done. This went on for quite some time.

Two weeks into it, the FBI was there on site. So you have Bloods, Crips, Gangster Disciples, Aryan Brotherhood—these prison organizations that have been around for decades, and I’ve never seen the FBI show up. Two weeks after the 12 Monkeys disruption began, the FBI was there doing ideological profiling, and they came and got me. I was taken away. There were three of us: myself, Blackjack Dzelajilja, and Les Dillon. They had us in the special management unit for about a year.

We were subjected to a special regimen that other prisoners had not been subjected to. It was really terrible: sleep deprivation, starvation rations, extreme cold, you name it. Under filthy conditions, they’d cut the soap rations in half and then cut them in half again. They suspended laundry service . . . It was terrible, and then they were messing with communications. They were actually photocopying all my outgoing mail for a year. They had thousands and thousands of pages. In fact, the FBI now has something like 12,000 pages in my files. The last time I contacted them, they said I could get a three-disc set for $40, which is roughly what it costs to buy the Sex Pistols box set. I would recommend, if you ever have the money, to probably go with the Sex Pistols; you can’t really go wrong with that.

As a result of all this, they sent us off to the super-duper-max. The 12 Monkeys materials, by the way, are still out there online somewhere. But if it could happen at Mansfield, it could happen at any prison, at any time. I think that’s what really upset them: that this happened seemingly out of nowhere, and it reminded them of just how powerless they are. At any time, they could lose control of an entire prison. Somehow I was responsible for that.

J11: What are some of the challenges you’ve experienced in prisoner solidarity, and what do you think we could collectively be doing better to support prisoners?

S: I don’t like to be critical anytime people are attempting to do something; I would prefer to be critical of people who are attempting not to do anything at all. Having said that, there’s been a focus in the past (and I’m not saying just anarchists—particularly with reformist groups) of attempting to get legislative things accomplished in order to help prisoners: trying to get reforms instituted through things like the Corrections Institution Instruction Committee in Ohio, and other things like this (lobbying efforts and so on). It seems that what all those have in common—that anarchists typically don’t do—is that this is an effort to do for prisoners what prisoners don’t do for themselves.

If there’s something we need to consciously focus on, it’s getting prisoners involved in their own liberation: getting us to realize consciously what power we possess, personally and collectively, and getting us to act for ourselves. That is far more beneficial, especially for a long-term project, than anything you see in this liberal/lefty/reformist approach to things; that has never really worked. I think we have that going for us; it’s our inclination to do that kind of stuff anyway. I would like people out there to not assume that prisoners aren’t down for doing something for their own liberation, but to assume that they are, and then to act accordingly. Like I said, those materials are still everywhere. They’re out there.

J11: Do you see ways in which June 11th can contribute to addressing these challenges? What are your hopes for June 11th this year?

S: It seems to grow in its visibility every year, and that’s something I like. Particularly among people who are doing things. It’s all good and fine, I suppose, if this starts to get coverage in mainstream media, and poor, delusional hierarchs all over the world start seeing some different kind of orientation or trajectory regarding prison and imprisonment . . . But I don’t know that that’s ever going to go anywhere. What I like is that it seems the anarchist community all over the world is becoming more and more aware, and more and more involved, in June 11th actions, activities, and events. I think the next step is to make every day June 11th; that would be cool. The more June 11ths we can have in a year, the better off I think we are.

It seems to me that it really is to everybody’s benefit to oppose this kind of pathology. Prisons, like the military, are a bulwark of this whole hierarch collusion. It’s one of the main pillars that prop the whole thing up. If we can take away the power to punish, then the whole system unravels, essentially. To be against prisons is really to be against the state; I’m hoping people start seeing the convergence.

J11: What are your broader hopes and visions for June 11th in the years to come and prisoner solidarity in general?

S: My hope is that a lot of things converge. Maybe this is too optimistic, but I’d like to think that we could succeed, and succeeding means the prison-industrial complex goes away (probably not without a fight) and the state goes away (probably not without a fight). My hope is that we develop strategies that cripple the systems of our enemies. That’s my hope.

J11: Are there any struggles or moments in the recent past that have inspired you?

S: A couple: there’s the 12 Monkeys thing, which I already talked about, but there’s also that callout that happened last September for the work stoppages that happened across the country. I don’t hold much stock in widespread work stoppage as a tactic or strategy in and of itself, but I think it’s something that can be used as a springboard for something else. For instance, now that the callout for the September work stoppage last year had pretty decent success—that identifies, for people out there, people they can work with in here (and maybe take things to the next level and the next level and the next).

There’s a current struggle that probably a lot of people don’t know about: the Palestinian hunger strike that’s happening in the occupier state of Israel. You have about 1,000 Palestinian hunger strikers. I don’t know how successful that’s going to be, because they’re up against a state that’s probably just as ruthless as Margaret Thatcher was. But the fact that there’s that kind of solidarity among prisoners there makes me hopeful that we can generate the same kind of solidarity with prisoners in this country.

J11: I’m really glad you brought that up. I haven’t heard much about it; it seems really impressive.

S: Isn’t it strange that here in the United States, we don’t hear anything that’s all that critical of Israel? Or anything that’s really sympathetic to Palestine? How strange.

J11: Are there any other projects or things you’re involved in that you’re excited about and would like to share with us?

S: I’m glad you asked. Right now, with the planned publication of Last Act as a book and How Emma Saved the World, I’m thinking ahead. I’d like to get Ohio published as a book. I’m thinking about this possibly for 2018, and then running for governor of Ohio at the same time, using that as my platform—getting enough funding from selling the book that we can get some bumper stickers and t-shirts and campaign pins and make a real fiasco out of the whole election process. That’s my next big dream.