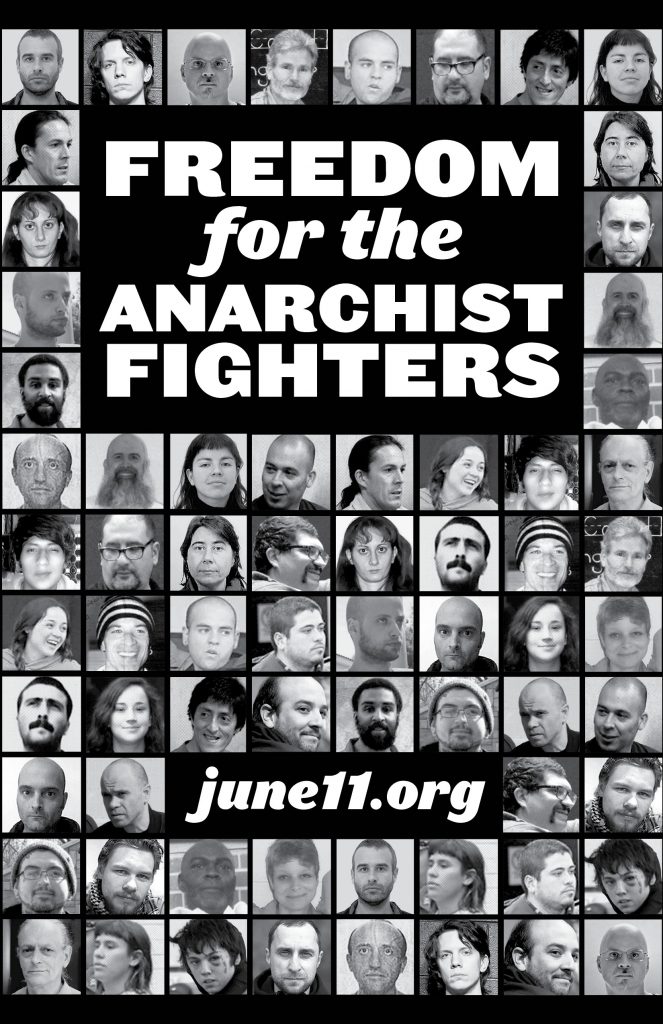

For the latest entry in our series of interviews for the June 11th International Day of Solidarity with Marius Mason & All Long-Term Anarchist Prisoners, we spoke to Josh Harper.

Josh is long-time animal liberation activist and former prisoner in the SHAC7 case. He has, for the past few years, been involved in archiving the history of animal and earth liberation struggles with the Talon Conspiracy.

We talked about his experiences in prison, what forms of solidarity meant the most to him, the challenge of post-release support for prisoners, the successes and failures of earth and animal liberation struggles, staying vegan in prison, Marius Mason, and learning to treat each other well as we fight for a free world.

JUNE 11TH: Can you start by telling us about yourself and your experience with prison and prisoner support?

JOSH HARPER: Absolutely. My name is Josh Harper, and I got active in probably about 1995 in Portland, Oregon with a group called Liberation Collective. Initially that organization was doing a bunch of voluntary arrest and civil disobedience type of stuff. My earliest encounters with prisoner support was actually something much simpler, which is jail support: people showing up to be there when you’re released, and making sure bail gets paid if that’s your wish, and so on. For the first many years of my activism that I was doing, environmental stuff and human rights stuff and animal liberation stuff, that was sort of the extent of my experience.

But a few years had gone by and I’d started to question the efficacy of voluntary arrest, especially I had actually done a little bit of jail time down in southern California. I was meeting people from outside of the small towns in Oregon where I had grown up, and I was talking to them about their struggles and their lives, and the idea that we would just voluntarily hand ourselves to the police to get the shit kicked out of us wasn’t very appealing to them. Seeing the end-logic of the voluntary arrest cycle – the actual jail time – I knew that it wasn’t something that I wanted to advocate for much longer. Unfortunately for me, that meant the tactics and strategies I took on became a little bit risky.

In the early 2000s, shortly after Bush Jr. declared his war on terror, I was a part of an organization called Stop Huntington Animal Cruelty, and we were indicted under terrorism statutes for a campaign we were running against a laboratory called Huntington Life Sciences. At that point I was sentenced to three years in federal prison, which I served at FCI Sheridan in Oregon. I want to say that I had tremendous prison support. I consider myself so lucky to be part of the communities that I had met through doing all sorts of different activism. There was actually one point early on in my sentence where I got called to the warden’s office, and I was told that I had to make the mail stop, that too much of it was coming in, and that because I was a terrorist, they had to actually stop and copy and read every piece. I basically told them, “tough shit!,”, that I was under no obligation to make the mail stop, and when I left his office, he handed me a hefty bag full of letters, and that was just one day’s worth of mail.

J11: Can you speak to the importance of prisoner support as part of the anarchist project or other liberation struggles? And specifically to the necessity of supporting prisoners with long sentences?

Josh: Absolutely. As anarchists, we are always going to be at odds with the state, and that puts us in a precarious position. It means that all of the state’s apparatuses are usable against us, and so if we want to keep our numbers, if we want to show our comrades that we love them, that we care about them, and that when they’re going through the worst of it, we will be there for them, we need to make good on those promises. And that means that, when one of us is in the arms of the state, we need to take care of people’s basic emotional needs, and try to get them through the American gulag as best we can.

That means putting money on people’s books, it means visiting them when possible, it means writing them letters, it means sending them magazine subscriptions and books and all of that. But it also needs to go past that. Prison is something that’s horribly traumatizing, I can’t imagine most people being incarcerated for very long at all without having some sort of long-term effect on their lives, and so one of the things that I would like to see going forward for anarchists and anti-authoritarians and liberationists of all stripes is that, when people walk through that gate, the support doesn’t end. Just because the prison sentence is over doesn’t mean that the trauma of prison has ended. And so I would really like to see us showing solidarity and supporting our comrades going forward by trying to work on things that do everything from help them to get housing and employment while they’re on probation, to projects that focus on long-term mental health care for former inmates. I think that is really the area that prison support needs to go next.

J11: Is there any sort of post-release support that you’ve seen that you thought worked really well? Or like a model or some sort of practices that would be good to suggest to other people?

Josh: Sure. Some of the organizations I often mention when I’m asked a question like this are organizations that support Irish prisoners after they’re released from prison. I don’t want to say that as an endorsement of the actions of the IRA, whose tactics and strategies I understand quite well but whose actions over the years I think at times have been pretty deplorable. But that said, the way that they treat prisoners in their communities is amazing. They help the families of prisoners, they make sure that everyone’s getting by financially, they pay for family members to take trips to prisons.

But then once somebody is released, they move into all this long-term area that I mentioned earlier. They make sure that people are able to get by, they make sure that all of their initial physical needs are met, that their medical needs are met, that if their probation officer is breathing down their necks, for them to have full-time employment or whatever, they make sure that all of that is taken care of. And the support never ends with them. Once somebody registers with one of those services, they continue to contact them, they continue to make sure they’re okay, and to ask what their needs are. Something like that is of course going to be quite difficult to put together, finding funding for former inmates in the United States. I mean you’re talking about a population that most of the citizenry never really thinks about or considers, and if they do consider them, it’s usually with disgust. So finding that funding and infrastructure is not going to be easy, but nothing worth having is. It’s definitely something we need to begin striving towards.

J11: Going back to your case or your history, and the fact that the case shows that doing aboveground work can face serious prison time – what implications does this have for public projects? And what can we do to mitigate this threat?

Josh: It’s really difficult when I talk about SHAC to give a complete picture of what the campaign entailed. On the one hand there was “Stop Huntington Animal Cruelty” and all of its various chapters and projects. Those organizations operated in an aboveground manner, they had public events and meetings that anyone could join. SHAC produced a newsletter and a website for which eventually six of us did prison time.

But SHAC was a bifarious campaign, much like the Black Panthers or many other organizations that proceeded it, people saw that there was a necessity for popular resistance and recruitment from the general public, there was a need to have a public face and an entry point. I definitely haven’t come to any hard and fast conclusions about what our case could mean for aboveground organizing. But I do know for myself, having watched so few of the people who actually participated in sabotage and the release of animals and so on, I’ve seen so few of them see any time, while the aboveground organizers in the group were sent to federal prison. It did sort of make me wish that I had reconsidered, and that perhaps I should have invested my efforts in those times into carrying out direct actions myself.

J11: The Green Scare and its subsequent string of snitching and harsh prison sentences severely damaged the Earth and Animal Liberation movements in the U.S. Are there lessons we can learn from this? And what do you think can contribute to a revitalization of these movements?

Josh: I definitely think that there are lessons that can be learned from what happened to us during the Green Scare. I also think that there are lessons that can be learned from the self-cannibalizing nature of the radical animal and environmental movements of the ‘80s, ‘90s, and early 2000s. As I watch this anti-fascist moment that we’re in and I watch a revitalization of interest and excitement around the idea of self-governing and anarchism, I’m very cautious because I think a lot of the young folks who are coming into it right now are missing a few facts.

One of those facts is that our opponents have the greatest possible incentive to shut us down. You’ll have to forgive me for making a Star Wars reference, but one thing I always tell people is that the empire will strike back. If you’re putting your finger in the face of the U.S. government, they’re not going to let it stay there for long before they try to rip it off. One of the things that has to be confronted immediately by a lot of these movements is how are they going to counter those efforts. What is going to happen when somebody is arrested, what funds are in place to make sure that people are supported once that occurs? What lawyers are sympathetic? Who can be called when there’s an emergency happening? These things need to be considered long before action ever takes place.

We should be participating in projects and movements that are more liberal and less radical than the ones that we would like, because we are going to need those connections later. I remember all during the SHAC campaign, we were of course very, very critical of the people who we saw as being unwilling to move forward with militancy. We talked about our disgust and disdain for welfarists and liberals and moderates all the time. But when the hammer came down, when all of a sudden the Department of Homeland Security was raiding our houses with Joint Terrorism Task Forces, when eventually we were all rounded up in a coordinated sweep with air marshals flying helicopters outside of our houses, the people we had spent several years alienating weren’t exactly eager to help us.

And so, I think part of the anarchist project needs to be infiltration in some manner of some groups that are friendly with organizations like the National Lawyers Guild and ACLU. People see these things as investing efforts and reformism, I see them as something quite different. I see them as investing in radicalism, to make sure that we build up the defense networks that we are certainly eventually going to need.

But beyond that, one of the things that we need to find a way to do is to be softer with each other. By the time that the Green Scare started to come about, and the Feds were looking for the people they wanted to flip, when they were trying to figure out who they were going to get to snitch on people, they had a lot to go by. Because movement infighting and ideological clashing were so dominant during that time period, by the time the arrests and grand juries came, there were already a lot of those folks who didn’t like each other, who weren’t on good terms, and who weren’t in contact with each other. For the folks that had been pushed out, or whose ideology had been ridiculed or whatever, I think a lot of them perhaps had an easier time turning on their comrades than they might have had people treated each other with a little more gentleness and a little more acknowledgement of the culture that we’re all raised in, and how that affects us, and how that keeps any of us from being politically pure. I would really like to see us preempt some of the tools that the FBI and others use to flip activists, by just treating each other a whole lot better.

J11: Can you talk about your experience being vegan while you were in prison?

Josh: Yeah, absolutely. When I was sentenced to prison, one of the things that was very, very important to me was that I didn’t want to let it change who I was to the degree that I was able. I definitely wanted to be in the sort of position where I wasn’t going to let the state force me to consume the products of the animals who I was trying to defend to begin with. I’d heard that when I was first sent down that all federal prisons offer a vegetarian option, so I was very excited by that, and thought maybe it’d be vegan, but very quickly I realized that that wasn’t the case. All of the vegetarian options at FCI Sheridan contained animal lactation or they had eggs, it wasn’t easy to stay vegan in there.

I received a little bit of criticism because my track record wasn’t perfect. One of the jobs I worked we were required to wear steel-toed shoes. After I showed up several times wearing canvas shoes that I had bought off of an inmate who had been transferred from a place where they could buy them, they said, “if you keep wearing these canvas shoes, we’re going to send you to the hole.” So I did eventually wear a pair of used leather boots. Going back to that ideological purity thing I was talking about earlier, I’d got out and I dealt with some criticism over that. It wasn’t something that I was happy to do, it was a choice that I had to make.

Looking at the history of animal rights and environmental prisoners in the United States, I think that’s something we need to be aware of as well. Once somebody is behind bars, they are often pushed to a point where they have to make decisions that they would never make in the outside world. Jeff Luers, I remember during the early days of his time at Oregon State Penitentiary for example, decided that pressing for vegetarian diet was taking up all of his energy, and not leaving him with enough time or energy to then focus on his appeal. And so he sent out a statement saying, “this is a decision that I’m making, I’m not happy about it, this is just sort of what the system pushed me to.” I was really disappointed to see so many people throw backlash to him for that. I don’t know, it goes back to that sense of being kind to each other, and taking care of each other, and not letting ideology overshadow our basic human kindness.

J11: You mentioned getting lots of mail and commissary money while you were inside, what forms of solidarity were the most important to you, and what forms could have been done better.

Josh: The form that was most important to me as far as getting through the hell of each week at that place was the visits. When people would come on weekends, I had a window into the outside world. I could talk to them about current events and the organizing that they were doing, I had somebody I could finally discuss politics with. Those visits saved my life, I hate to imagine what my life would had been like if they had not occurred. A lot of those visits were made possible by my support group raising money, and helping pay for my mother to come, for old friends to come out, and of course members of my support team themselves. They would come almost every weekend. It gave me life in a place where, you know, you sort of feel like you’re in stasis. The world’s going on without you on the outside, and you’re just trapped in a place where time doesn’t move.

So those visits were the most important thing, followed close by letters. I loved hearing from people from around the world, and getting a glimpse into their lives. I loved looking at the pictures they would send, and getting to see sights that I would never get to see behind bars. People would go on hikes or they’d go drift-boating, or they’d see some gorgeous vandalism in the city, and they would send images of it, and it really did keep me going.

But there were parts of support that were a little bit lacking, and especially once again upon my release. Part of that was because the movement wasn’t really trained, I think, to understand the initial needs of a prisoner post-release. When people would come to me and say, “How are you doing?” I would say, “I’m doing great!” Because in the first time in three years, I was able to be around friends and family and the outside world. I had freedom of movement, I could cook good food at my own place, and everything seemed exciting and wonderful. And so, in some small way, it was my own fault that people didn’t offer post-prison support because I seemed so happy.

But one of the things that we need to learn is that a lot of inmates, after incarceration, feel that initial rush of joy and the answers they would give to questions like how they’re feeling about their incarceration are going to be overwhelmingly positive, because they don’t want to think about it. They don’t want to reflect on those things, they don’t want to share the hell that they went through, so they’re going to say, “I’m alright, I’m okay.” I wish that we had a little more knowledge that that would be the case. I think the people supporting me really wanted to do their best, in fact I know that they did. But now with the little more knowledge that we’ve gained since, yeah, I can see that the deficiency happened when I left prison. Moving forward, I think that Anarchist Black Cross chapters and so many other prisoner support projects are going to need to acknowledge that, and work to fix it.

J11: Are there any ways that June 11th can address some of these deficiencies? And do you have any hope for June 11th this year?

Josh: Oh, I have hope for June 11th every year. And part of the reason I hold that hope in my heart is that one of the very first people that ever reached out to me when I was facing federal charges back in 1999 related to a grand jury that was investigating the Earth Liberation Front was Marius Mason. They sent me e-mails and they raised funds for me out in Indianapolis, and they sent pictures from a bake sale that they held to benefit my support fund at the time. And so when I think of Marius in there, and I think about June 11th, I want June 11th to be very successful because I want this wonderful person, who has given his all in order to save life on this Earth to make it a better experience for everyone here, to attack the industries that are attacking us, I want to make sure he gets the best possible support.

I want to make sure that there’s lots and lots of attention given to his case. That is my ultimate hope for June 11th organizing. And I do think that the folks who organize June 11th have an opportunity to begin to innovate new methods of prisoner support, to think beyond just the letters, the commissary funds, and such, and to begin asking broader questions. How can we support inmates’ mental health while they’re still in, how can we support it when they’re out? How can we expand on our ability to help our comrades?

And I think that can also be done with an eye towards movement-building, I think it can be done in such a manner that people see we’re a community that supports each other, that when the going gets tough and the chips are down, we step up, and we do our utmost, we don’t back away from the state, we don’t turn on each other, we don’t snitch. I think that all of that is something that can be done in a really high-profile way with June 11th. My understanding is that there are still people working on organizing June 11th events around the world, and hopefully all of them are trying to get that message of struggling alongside each other, and making sure that our efforts are as good as they can be for our friends behind bars.

J11: What are your broader hopes and visions both for June 11th and for prisoner solidarity in general?

Josh: [laughs] Oh gosh, I don’t know. It’s difficult to talk about my hopes during such a dark time period because they stand in such stark contrast to the world as it actually is. It sounds naïve, I suppose, to say at this point, that I’d love to eventually see an end to authority. I would love to see an end to the interpersonal oppressions that we cast at each other. I’d love to see an end to surveillance and the police state, I’d love to have some sort of ecological sanity, I’d love to see us treating the other creatures we share this planet with in a manner I think that’s more consistent with all of our personal ethics.

It’s difficult when you look at the current regime and you see fascists and Nazis openly declaring themselves and marching in the streets. It’s difficult to believe that anything better is possible when we’ve already come this far in the opposite direction. But I think history provides us a lot of examples of people who had enough, who were tired of being told that the power wasn’t theirs. They were tired of being told that they didn’t deserve food, or new shoes, or clothing, that they didn’t deserve clean water or clean air or clean soil, that all of those things only belonged the hands of the few. And eventually they said, “no, fuck no, fuck no, we’re going to take it back!” I want to see that, I want to see that rupture, that breaking point, where people realize that they’ve been lied to, that they do have the power, and that they can resist. And they can do so in a manner that they’re directly participating in, that they’re not waiting for some savior from the Democratic Party to arrive, or another person to throw the first stone. I want everyone to realize that revolution is participatory and that it’s crucial that we all take part. I know that was a little rambling, I hope it actually answered the question.

J11: On that note, are there any struggles or moments in the recent past that have inspired you?

Josh: Oh my goodness, yeah. One of the things I work on right now is a website called The Talon Conspiracy. It’s been on hiatus for just over a year, but we’re about to come off of it. One of the things we do is archive old animal rights publications and environmental publications. The next thing that we’re going to put up is a book called The Old Brown Dog, which is about the Brown Dog riots in the early 1900’s in England. One of the really exciting things about that time period is that you had a feminist movement that was beginning to happen, that was coming out of the movement for suffrage, but was more radical. It was women who were realizing that the vote alone wasn’t going to bring them to freedom. You had members of the Britain Union to Abolish Vivisection, which was an organization originally founded by Francis Power Cobbe, a queer woman whose politics were very socialist-leaning. Most of the rank-and-file of the organization I wouldn’t say were as radical as she was, but there were definitely radicals amongst them. And you had labor unions, all of these organizations formed a coalition that actually physically fought with vivisectors and police in public plazas in England after vivisectors had actually rioted and destroyed a statue of Brown Dog, who was a monument to victims of vivisection.

History has so many examples of people who were outraged, but of course it’s not just historical stuff. It’s the folks nowadays who are rescuing people from collapsing buildings in Syria, and fighting back with force of arms against Assad’s regime. It’s the people who just recently in Greece went to the leader of a fascist organization’s apartment and broke in, and trashed the place. Every single day there are people out there who are committing acts of resistance, and are showing that this does not have to be tolerated, that we can answer this challenge. Anyway, it’s definitely one of joys in my life, to read about the past examples of that, but I get so much more joy to see current examples.