From Contra Info

Der 11. Juni ist ein internationaler Tag der Solidarität mit Marius Mason und allen anarchistischen Langzeit-Gefangenen. Ein Funke in der ewigen Nacht, staatlicher Repression. Ein Tag, an dem vorgesehen ist, diejenigen zu honorieren, die uns weggenommen wurden. An diesem Tag teilen wir Lieder, Veranstaltungen und Aktionen, um unsere gefangenen Gefährt*innen und Nahestehenden zu feiern. In vergangenen Jahren waren die Feiern zum 11 Juni international und breit gestreut – von Selbstversorger*innenpartys mit Freund*innen, bis zu verschiedenen inspirierenden Angriffen; von Spendenaktionen und Briefschreibeabenden für Gefangene bis hin zu den nicht erzählten und unbekannte Wegen, wie wir die Flamme am Leben erhalten.

(…)

Update zu den Gefangenen

Während des vergangenen Jahres waren unsere inhaftierten Gefährt*innen, mit unversehrter Integrität, den kalten Augen und gewättätigen Händen des Staates ausgesetzt. In Chile versuchte Tamara Sol aus dem Gefängnis zu entkommen und wurde dabei ernsthaft verletzt und überführt: Zunächst in ein Hochsicherheitsgefängnis in Santiago und dann zum besonders brutalen Llancahue Gefängnis in Valdivia. Die „Casa Bombas 2” wurden beendet. Juan Flores wurde für mehrere Bombenanschläge in Santiago schuldig befunden und zu 23 Jahren Gefängnis verurteilt. In Deutschland wurde Lisa zu mehr als 7 Jahren Haft verurteilt. Sie wurde für schuldig befunden eine Bank in Aachen ausgeraubt zu haben. Im Februar wurde sie in die JVA Willich II überführt. In den Vereinigten Staaten, ging Walter Bond für sechs Tage in den Hungerstreik. Er forderte vegane Mahlzeiten, ein Ende der Eingriffe in den Briefverkehr und die Überführung nach New York, wo er nach seiner Entlassung leben möchte. Als Vergeltungsmaßnahme ging es für ihn in die „Communications Management Unit“ in Terre Haute, Indiana. In Griechenland, unternahmen Pola Roupa and Nikos Maziotis einen Hungerstreik für fast 40 Tage. Sie forderten bessere Haftbedingungen, und längere Besuchszeiten, so wie die Abschaffung der äußerst repressiven C-Typ-Gefängnisse. Dinos Yagtzoglou wurde verhaftet und ist wegen einer Briefbombe angeklagt, die einen früheren Premierminister verletzte. Sein Widerstand hinter Gittern löste einen Aufstand in drei griechischen Gefängnissen aus und garantierte seinen Forderung ins Korydallos Gefängnis überführt zu werden.

In den Vereinigten Staaten braucht der trans*anarchistische und Öko / Tierbefreiungs-Gefangene Marius Mason mehr Briefe. Er mag es, Artikel über Tierrechte, Umweltaktivismus, Widerstand zur „Alt-Right“, Black Lives Matter und andere Gefängniskämpfe, zu bekommen. Das „ Carswell Federal Medical Center“ in dem Marius die letzen vergangenen Jahre einsitzt, ist eine bekanntermaßen restriktive und brutale Eintichtung. Zur Zeit verweigern sie ihm medizinische Unterstützung für seine, ihm zugesagte Geschlechtsumwandlung und ebenso angemessene Wahlmöglichkeiten für vegane Mahlzeiten.

Der 11. Juni ist eine Idee, nicht nur ein Tag. Jeder Tag ist 11. Juni. Und Ideen sind unverwundbar.Last uns das restliche Jahr mit Leben erfüllen und forführen, das Leben anarchistischer Gefangener zu feiern, indem wir ihre Kämpfe an ihrer Seite gemeinsam mit ihnen fortführen.

In aller Kürze: Es ist ein Aufruf, als rufen wir euch auf. Der 11. Juni ist das, was ihr daraus macht. Folgt euren Herzen und erfüllt die Welt mit wundervollen Gesten. Es gibt keine Aktion, die zu klein oder zu groß ist.

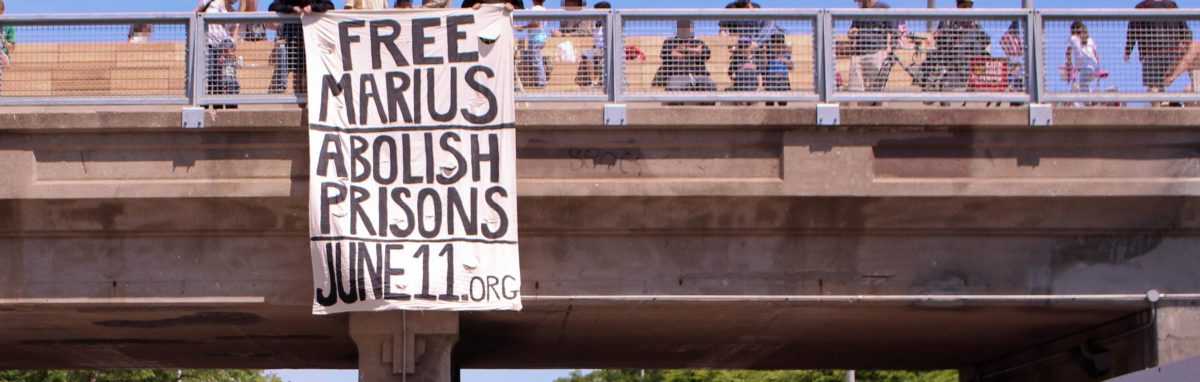

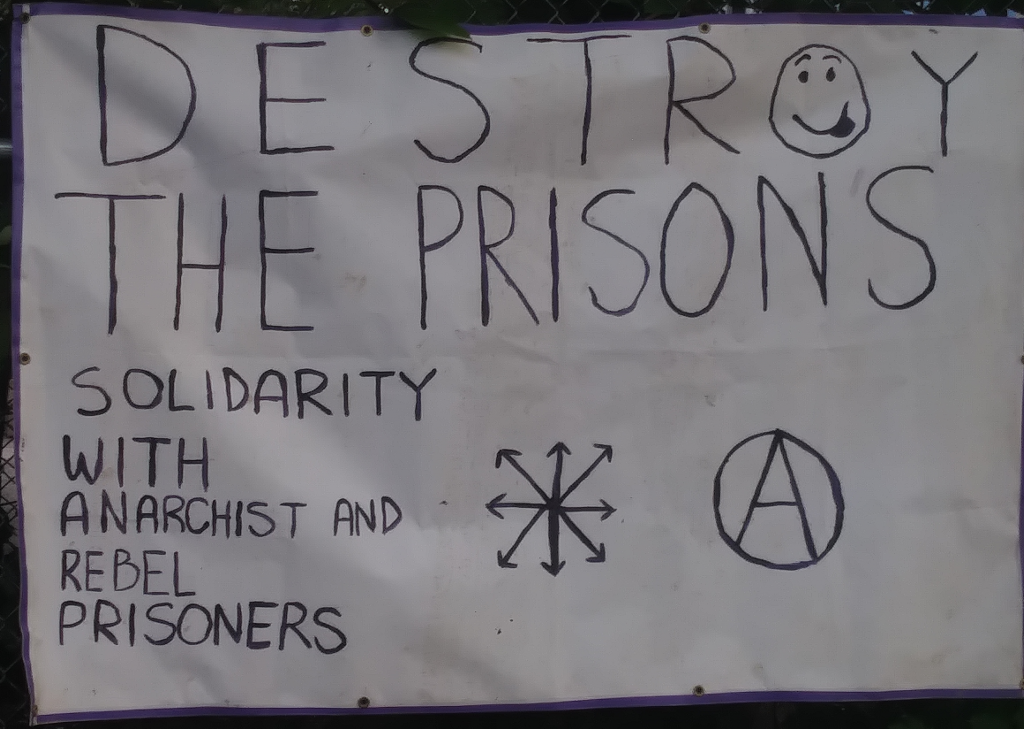

We’ve been wheat-pasting around town this month leading up the day of solidarity with long term anarchist prisoners. On the 11th we dropped banners for the morning and evening rush hours, “Support Marius Mason & Prisoners” and “For a world w/o Prisons”. The next night we reached out to Days N Daze a touring folk-punk band and distro’ed their show. Passed out lots envelopes, stamps and June 11th prisoner statements to a bunch of interested folks who had never written a prisoner and were excited to start! To Eric King, Marius Mason and all those behind bars, solidarity and love from the he(a)rtland.

We’ve been wheat-pasting around town this month leading up the day of solidarity with long term anarchist prisoners. On the 11th we dropped banners for the morning and evening rush hours, “Support Marius Mason & Prisoners” and “For a world w/o Prisons”. The next night we reached out to Days N Daze a touring folk-punk band and distro’ed their show. Passed out lots envelopes, stamps and June 11th prisoner statements to a bunch of interested folks who had never written a prisoner and were excited to start! To Eric King, Marius Mason and all those behind bars, solidarity and love from the he(a)rtland.