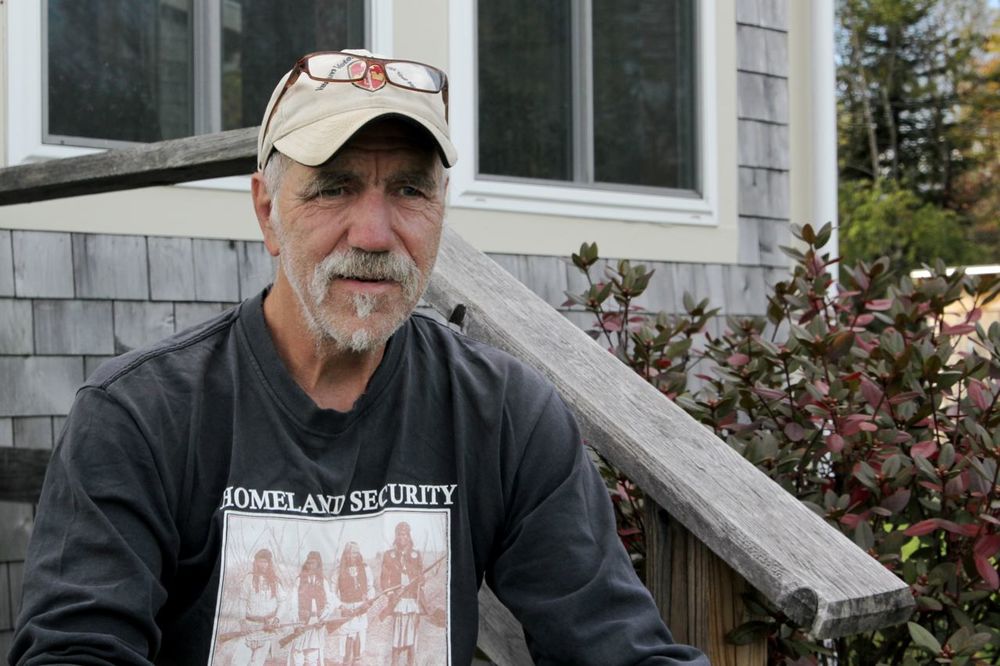

In this interview for the June 11th International Day of Solidarity with Marius Mason and all long-term anarchist prisoners, we spoke to Ray Luc Levasseur, former political prisoner and member of the United Freedom Front. We talked with Ray about his history with anti-prison organizing, going underground to wage armed struggle against the state, fighting for parole for political prisoners, solidarity he received while behind bars, supporting aging and ill comrades behind bars, having children while underground, and how to support his imprisoned comrades Tom Manning and Jaan Lamaan.

For more from Ray, check out previous interviews with The Final Straw Radio and Kite Line. To get in touch with Ray about supporting the remaining United Freedom Front prisoners, email him at rayluclev [at] gmail [dot] com. You can write to Tom Manning or Jaan Lamaan at the addresses below, or check out NYC Anarchist Black Cross’s prisoner listing for the most up-to-date addresses.

Jaan Laaman #10372-016

USP McCreary

Post Office Box 3000

Pine Knot, Kentucky 42635

Thomas Manning #10373-016

USP Hazelton

Post Office Box 2000

Bruceton Mills, West Virginia 26525

June 11th: Today we’re speaking with Ray Luc Levasseur. Ray, thanks for joining us. We won’t make you go through your whole biography, as fascinating as it is, because you already have done some really good interviews and pieces that go through all of that. But with that said, would you like to say a few words of introduction?

Ray Luc Levasseur: Greetings to whoever is reading or listening to this at some future time. I don’t want make any assumptions about what people know about me or the United Freedom Front or any of my co-defendants and comrades. I was doing a public speaking engagement at a library the other day and I got asked this question I get asked quite frequently. People want to know how you get from growing up in a small mill town in Maine to being on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List for underground activities targeting the government and corporate criminals. Like you said, I think you’ve got material about some of my background, but I’ll just touch on a few points that were significant crossroads for me early in life, that proved to be significant life experiences that were the foundation of the political person I became.

One is I grew up as part of an ethnic minority in a mill town in Maine, and that minority being French Canadian. Growing up in that ethnic minority, in the situation I was in at the time, formed my early perceptions about people who are denigrated and exploited based on their ethnicity or race. I was born and raised in a mill town, meaning textile mills and shoe factories. Our backs were right up against them. So I was born in a particular class and I had no politics at this time growing up, but I had the gut sense that something is wrong when the majority of people in the community you live in think you are inferior because of your ethnicity. And because that same ethnic group made up the significant portion of the exploited workers where I grew up.

So that’s what I took with me when I left Maine at the age of 17. And eventually, like a lot of people where I grew up with a particular ethnic or racial background, and being from a particular class, we were looking at two things: working in very exploitative situations and being used as cannon fodder in the Vietnam War. That’s as far as I go back, I’m almost 72 years old, for anybody reading or listening to this, to give you an idea of how far back my roots go. And so between the ages of 19 and 23, I already experienced working in some pretty degrading situations, and I ended up in the military, in Vietnam, in the war.

After I came back I was living down south in Kentucky and Tennessee, catching a five year prison sentence in Tennessee State Penitentiary after my first activist experience which was with the Southern Student Organizing Committee, which was a southern-based regional organization. And so I ended up in one of the worst prisons in the country, Brush Mountain Penitentiary. And all this takes place between the time I’m 19 and 23, so those were the formative experiences. After I got out of prison in Tennessee, I just went deeper into activism.

The next group I was involved in was Vietnam Veterans Against the War. But in the early ‘70s the war was literally dying down, and because by this point in my life experience and my studies and my interactions with early people, my early activism down south, I’m connecting the dots. And I realize that this is a system that we’re up against, that ending the war per se is not going to end war, and it’s not going to end the system of capitalism and imperialism. So I left Vietnam Veterans Against the War as the last American troops came home, and refocused my attention on prison and criminal justice issues. This was around the time of the first anniversary of the Attica rebellion in 1971.

The group that I eventually worked with was called SCAR, and it was a group that was founded primarily by formerly imprisoned people, otherwise known as ex-convicts. Our main chapter was in Portland, Maine, but we also had a prison chapter. Part of our strategy was patented after what the Black Panther Party was doing at the time, its Survival Pending Revolution programs. We were trying to be community-based, recognizing that criminal justice issues and prison issues are not going to be adequately dealt with in a vacuum, that you had to deal with larger social changes as well. We tried to implement programs on a community level that addressed some of the issues and problems that poor people in the community were experiencing.

For example, we were told there was a big problem with bail money, especially with young people being jailed because they couldn’t make a $75-100 bail. That was a slippery slope to spending the rest of their life in a revolving door of the criminal justice system. We started a community bail fund, we provided free transportation to prisons – everything we did was cost-free. The idea of the programs was to get people directly involved in resolving some of these problems faced by the community. It was sort of an elementary step of self-empowerment to demonstrate that we could resolve some of these issues ourselves as we step up towards broader social change, rather than just throwing the rhetoric out there. Trying to demonstrate that we could actually do things.

We had a martial arts program, we had our own newspaper, we eventually opened the Red Star North bookstore which had a books to prisoners program. Of course, all of this attracted the attention of the police, and we had some run-ins with them that were not pleasant. It was towards the end of that time that I went underground, in late 1974, and didn’t re-emerge until I was captured in 1984.

J11: When I was listening to your interview with Final Straw Radio from last year, I was really struck by these activities that you’re describing now, that you were doing shortly before you went underground. Running a bookstore, the books-to-prisoners program, teaching classes in jails, doing newsletters, doing speaking events; all these things sounded really familiar to me. Lots of those things are things that I and so many people I know have done or are doing, yet at the same time this next step of going underground and committing to armed struggle seems really foreign and rare.

Most “political violence” these days comes from the Right. Since the Green Scare really devastated parts of the environmental and animal rights movements that were committing arsons and other such attacks, there’s been very little coming from the Left or from anarchists. What do you think about having on the one hand such a similarity in our activities, and on the other such a vast difference? Or is that similarity just superficial?

R: Well, similar in activities in terms of what we were doing then and what’s being done today – some of what I’ve been talking about was 50 years ago, 40 years ago. I was released from prison in 2004. I returned to Maine and there was not a lot of organizing going on. There was not anything I would call a movement in Maine, or New England for that matter. There was motion, there were things happening, but motion is different than movement. I saw that people were pretty fearful. I’ve asked this question you’re asking about the similarities to myself, because in the time I’ve been out since 2004, I’ve been looking for the same key everybody else has been looking for: what works and what doesn’t.

I think some of the same things that were being done by the Black Panther Party or groups like SCAR 40-50 years ago, some of those are fundamental to any kind of grassroots organizing. You’ve got to communicate to people. The whole purpose behind the survival programs was to get beyond the rhetoric. There’s plenty of groups that have rhetoric, some even have good rhetoric, but if it’s just rhetoric, if all you’re going to do is put out the party line, sell a newspaper or tracts that support that, but not doing anything concrete, then that’s not going to work. But, here I am all these years later, I’m still doing a lot of public speaking. I spoke at a public library this past Tuesday, and about 25 people were there. That’s advocacy. I’m almost 72 years old, so I would say I do more advocacy work now than I did in the past. Advocacy has always been part of organizing, but advocacy itself doesn’t always include organizing. I do public speaking because I find that people don’t know a lot about an issue that’s dear to me, which is political prisoners. They still don’t know a lot about mass incarceration and solitary confinement.

So that public educating and consciousness-raising, and interacting with the public that way, how you do it and everything, there’s different ways. But basically you have to recognize the need that if you don’t change more the people’s thinking about certain issues, then you’re not going to be able to do much organizing. So that’s still a fundamental part of what I do and other people do. But another thing I was just involved with is legislation, and I’ve been involved in the last 18 months and in particular it was Ban the Box legislation. I found myself working with the first black woman elected to the state legislature in Maine, if you can believe that it took this long.

But ironically she’s the daughter of the first black legislator back in the early ‘70s that was elected in Maine to the House of Representatives. And I was doing some legislation with him 45 years ago when I was with SCAR. It was never priority work with SCAR to do legislation, but what submitting certain bills around prisons did for us was that it gave us access to the media. We could do press conferences, we could do public hearings when the bills came out. We never thought we would get them passed and for the most part we didn’t. We didn’t put a lot of effort into it. It was just another tool that we could get out there and engage people with.

And here I am now, decades later, and I really felt that this Ban the Box bill offers an opportunity to bring people in where they would actively engage in organizing around this bill, the issue that this bill deals with, Ban the Box. Because I can’t justify doing legislation unless there’s a corollary effort in the community, a parallel effort in the community to get out there and do public education and organize around issues presented in the bill. Because if the bill fails, you’ve done some ground work and you can come back for another shot at it if you want, or you can go back to those same people and try to get them involved in other criminal justice issues, other jail issues. And what happened was after 18 months, that bill eventually in one form or another…the short of it is: I became terribly disappointed, because there wasn’t an adequate corollary effort outside the legislature. So it ended up being strictly me, and a legislator, and somebody with the National Employment Law Project basically carrying all the weight on this bill. And this is just coming to an end now, and I have to really seriously question whether I want to do that sort of thing again, whether I want to get involved.

And I have done the solitary confinement bill, which did have some success 7 or 8 years ago. One of the reasons I got involved with that is it had generated a lot of public conversation on the issue, and some movement towards reducing the numbers in solitary and all the abuses that go with that. And so this, I was hoping to do something along the same lines, and it didn’t work out, and I really question whether I’ll do another piece of legislation. So, what works here in Maine may not work in Massachusetts, everything is based on time place and conditions. We have social media today, I don’t use it, and I recognize it’s a potentially important tool. And maybe if we had somebody a little more technically savvy who would have used this in the latest legislative effort, maybe we could have done more with it.

So that’s two examples of public advocacy and engagement, where I was just speaking at the public library, I was speaking at the public library 40-45 years ago, that still needs to be done. But the question of legislation and where that fits in the larger organizing scheme, and how to move things forward, and how to build a movement out of certain motion, that’s where some of it’s going to work today, and some of it won’t work today. Some of it that was done decades ago may work today with modifications, with changes. You’re going to have to remind me of the second part of your question.

J11: I think you largely spoke to it, I was just thinking about the similarities between a lot of what’s happening now and what you were doing 40-50 years ago. But also how it was so different with going underground.

R: Yeah, underground is much different. I love community organizing. I consider myself at this latter point of my life more of an advocate than an organizer. Where, in the distant past, I definitely saw myself as an organizer – of which advocacy is a part of an organizer. I’m finding a lot more advocacy these days, and a lot less organizing frankly. And that’s not just here in Maine. I was just in Boston and a month before that I was in New York, and I’m finding this problem in other areas as well. I think there’s a lot more advocacy going on than there is organizing. That can give some people a distorted picture of what you’re about. If you do different kind of advocacy, especially on social media and stuff, or even in print, it can create a distorted picture of how strong and how deep your particular organization or movement is.

But as far as going underground, you’re talking apples and oranges now. But I can tell you this, we ran into a lot of problems the first year underground. There were a lot of challenges, and it was very dangerous. Early on, I questioned whether I had made the right decision, and the fact was that I missed the organizing I was doing while I was underground. I used to teach martial arts programs in the projects, I taught women’s self-defense classes. We taught children, and worked on a community bail fund. I was very involved in all the programs we were doing and all of our work, and then all the sudden it just evaporated. I had to completely shift gears to another type of political work.

And all of a sudden, instead of showing up at the projects at a particular time with thirty kids waiting for me, or going to the Maine state prison to visit someone in segregation under the auspices of the Pine Tree Legal Association at that time: I’m not doing that anymore, it’s all gone. Early on I was questioning whether I had made the right decision to go underground because of problems we were having. It was a difficult transition period before we got our “sea legs” so to speak, and moved on. Because by that time I was committed, and there was really no going back.

J11: On the topic of the United Freedom Front, the UFF differed from many largely white anti-imperialist armed struggle groups of the ‘70s and ‘80s, in that it came more from a working class background and the prison movement. In fact the group’s original name paid tribute to white anti-imperialist Attica brother Sam Melville, and Soledad Brother George Jackson’s younger brother Jonathan, who died in an attempted liberation of black rebel prisoners in California. What effect do you think your background as an ex-convict had on the priorities of the UFF, and do you think the group’s orientation differed from similar groups whose origins were in the student movement.

R: Yeah, as I said earlier, ethnic background, what that means, where I grew up as part of a group that’s considered inferior by the dominant Anglo-Protestants, and growing up in a particular class. I was 17 years old, I was making shoe heels in a factory in shit conditions for shit wages. I didn’t have any political analysis of it, but I had a gut level analysis that something was wrong. Then, the war and prison between the ages 19 and 23. So through some very formative years that had a lot to do with my thinking and the fact was that those of us who were underground, like Tom Manning who is one of my co-defendants still in prison, he was a Vietnam vet also. And he had been in prison like me. And others that were part of the UFF had been in prison, who had been anti-war activists.

And all of us had working class roots. Whether it was the earlier formation underground or the later UFF, those life experiences and background roots had everything to do with what we thought our priorities should be, in terms of our actions. Compared to the Weather Underground for example, which came out of campuses. Those of us underground that were charged with UFF actions, there was not a college degree in the group. Actually I think that’s one of the reasons of several that the FBI was so batshit about us while we were underground. We were so successful at eluding capture and remaining active the whole time. I mean how many other groups can you look at that were actively engaged in armed resistance over a 9-10 year period? There’s not many out there.

So we were a really bad example in the FBI’s eyes because we didn’t have the kind of resources a group like Weather Underground had. We didn’t have money coming in from families and professional friends and whatnot. If we were going to have a payday, if we were going to fund our activities, we had to go out and get that money. There was only two ways to do it, one was to work wage labor, which a lot of people don’t realize that for quite a number of years we were working wage jobs, difficult wage jobs. The other way was expropriations. Groups like the Weather Underground really didn’t have to resort to expropriations because they had a pipeline to funding that we didn’t have. Because we were engaged in early underground actions around prisons and also Puerto Rican independence and the release of Puerto Rican prisoners being held at that time.

Actually if you look going further in time to the UFF actions, if you look at all the actions credited to us underground, no matter what the political focus is, they all involve the release of prisoners one way or another. Whether it’s Puerto Rican nationalist prisoners in the ‘70s, whether it was Nelson Mandela and all the political prisoners held under the Apartheid system in South Africa in the ‘80s, release of prisoners from solitary and segregation. Freedom around the Central American wars that were raging around that time, demanding release of political prisoners as they were starting to accumulate in this country. That was always on the agenda, always in the communiques that came out of our group.

J11: You spent almost 20 years in federal prisons. What reflections do you have on prisoner solidarity from that time? And how did it change as your sentence went on? Was there a certain kind of support that felt most important, and anything that could’ve been better?

R: It was exactly 20 years to the day. Probably around 13 years of that was in some form of isolation or solitary. Including years at Marion, which was the federal government’s lockdown prison, the prison that replaced Alcatraz. And then when they opened ADX which is the present supermax, the one they’re still using now, those of us at Marion went to ADX. As you may or may not know, I represented myself in two major cases associated with UFF actions. But in a way, I was fortunate that I got a significant amount of support, but there’s a difference between individual support and supporting the group or supporting political prisoners. Because there was a lot of political trials going on in the 1980s. I was involved in two major trials.

I really got to distinguish between the individual and the group support, or the larger base of support for all political prisoners, whatever movement they were coming from at the time. So you’re talking Puerto Rican independence movement, American Indian Movement, former Panthers, former BLA, anti-imperialist political prisoners, and others. Especially throughout the course of the ‘80s and early ‘90s. We had two major trials, one in New York, one in Massachusetts. There were other trials as well, but those were the two main group trials. So we did what everybody else in that situation does, we contacted friends and acquaintances about putting a defense committee together. By the time we got to the second trial that committee was known as the “Sedition Committee,” because we were being tried with sedition among other charges.

And that was much needed support, but it was a small committee and its focus was on us and our trials, primarily. And what was going on at the time was that’s what other groups were doing. A small defense committee would tend to form around however many people were involved in a case and their trial, and while there were fraternal relations between some of these committees, the fact was that some groups and some individuals received much more support than others. For example, you go back to the 1980s, Leonard Peltier’s was the biggest campaign at that time, while other political prisoners were getting barely any support at all.

So in discussions between some of the political prisoners and supporters outside, there was an effort to bring all these committees and support groups together. The idea being to bring them all together and share resources, we could become stronger and start to build a movement that would represent all political prisoners in the United States. In theory that was wonderful, I supported the idea initially. In the early ‘90s it led to the formation of the group Freedom Now, sort of a coalition with reps from these various defense committees and others. It didn’t last but about two years before it collapsed. And I felt the weight of that because when it collapsed, I was done with my last trial, and the defense committee that had formed to support us first in the New York case, and then in the sedition case, they had looked towards Freedom Now too as something to put their energy towards. So when Freedom Now collapsed, we were left with no defense committee. It wasn’t until 1998 that a group called Jericho was formed, to try and fill that vacuum left by the demise of Freedom Now.

The fact was that we were still in the same situation: a lot of small defense committees, or in some cases prisoners that had no formal committee at all, scrambling to get some kind of support. So Jericho was initiated, and the intent of Jericho was to pick up where Freedom Now had left off, which was to see about merging all of these defense committees and support committees and try to build one solid group to build one solid movement to support all the political prisoners. Well, Jericho is still around. I was in New York last month for the commemoration of the 20th anniversary, but Jericho has never reached that goal, and it hasn’t reached its potential. It’s done some much-needed work, I’m glad it’s there for various reasons, but it’s way short of achieving that goal.

So right now, in 2018, we’re in the same situation we were when I was first captured in 1984, which is some political prisoners get a lot of support and have a large organized group behind them, probably most significant now is Mumia Abu-Jamal, probably a second is Leonard Peltier. And the one I think is the sterling example of what can be done and should be done on a larger scale, if we could emulate it, is the Puerto Ricans. Because when I was in Boston last week I met with Oscar Lopez Rivera, who is the last of the prisoners from the Puerto Rican independence movement released, a year ago this May. I think what the Puerto Ricans did to get all the FALN prisoners out, and Oscar being the last one, is if we could recreate the movement they built to get those prisoners out on a larger scale, whether it’s covering anarchist prisoners, communist prisoners, anti-imperialist prisoners, Black nationalists, whatever, we would be on our way, on much solider footing, to support our prisoners inside. Because there’s a lot of types of support they need before you get that glorious day when they are released. But so far we have not been able to do what the Puerto Ricans have done.

Now as far as individual support, I was fortunate. Because the UFF prisoners were not big names like in the Weather Underground. We were not big names in the Left, we were not marquee names, but some of us had long histories of political organizing, and there were those who remembered us. The earliest defense committees for us were people we had been politically active with before we went underground. Going back to my first experience organizing in the south, and I still had connections with folks down here. So I was fortunate I had that kind of history, and by representing myself as my own lawyer in these two major trials, I had a relatively high profile. So as the media started looking at these trials, one of the things that drew them was the defendants who represented themselves, because I was representing politically what we stood for, what our actions stood for. We started to get more media coverage, I started writing articles that were published, mostly in the lefty press. All this generated a correspondence. I was fortunate from the earliest days I was in until 20 years later, the day I walked out, that I had a really life connecting correspondence with people all over the country, and sometimes in other countries outside the US.

That gets us to another issue, of how you survive 20 years in prison, including all this time in solitary, and one of the most important aspects of survival was that connection to people outside, the large majority of whom were activists. So if I was writing to someone in Okie Pinokie, Oregon or Des Moines, Iowa or New York City, I am connected with these people both personally and politically. I know what’s going on politically in the neighborhoods and communities and the state that they’re living in because they keep me informed, and I know what’s going on in their personal lives. I know what kind of questions they have about which way forward and engaging in that kind of communication with them.

So I was very fortunate in terms of individual support. Individuals that supported me and sometimes small formations like the Anarchist Black Cross, just to cite one. And people that were organized with other organizations kept me supplied with books, newspapers, political tracts. The correspondence was invaluable. They provided me with an outlet for my writing. A lot of this is pre-internet days, but I had connections. I would send out an article, it would get printed, it would get distributed, and next thing I knew it would show up in a publication. It would be read or discussed on a radio program. This kept me from disappearing, because there’s a reason they put me in Marion first and then ADX, because when they bury you in prison, they’re trying to disappear you. When they bury you in a supermax prison, they consider you a problem. They considered me a problem and the problem was that I was still the same political person I was the day I was captured. They didn’t want those kinds of politics spreading inside the federal prison system, so they put you in solitary and isolation for years on end. And to break that kind of isolation requires an extraordinary effort on the part of people on the street to prevent that from happening. Number one, I think that kind of individual support I received from people and small groups absolutely needs to be done.

You can’t let political prisoners get abandoned and abused inside these prisons. And it was people, regular folks that kept that from happening to me, and kept me connected. It also should be part of any group’s political program that purports to support political prisoners. You can’t leave a political prisoner in a cage, in a prison, where that person can’t even afford postage stamps to stay in touch with people, or buy a pair of shoes to put on their feet. So like I said, it’s very disproportionate the support political prisoners get. Some political prisoners don’t need any money for postage stamps or art supplies or books. But others are struggling. There are many types of support that can be provided, and it should be provided by any individual that feels they can do it, and recognizes it needs to be done, and also it should be part of more formal support of any organization that does any kind of prisoner support work.

J11: From Kuwasi Balagoon’s death from AIDS-related illness in prison in 1986 to your own comrade Richard William’s death in 2005, the issue of health and aging in prison continues to be an important one. As supporters of long-term prisoners, including many who are entering old age behind bars, these are issues at the forefront of our organizing. Do you have thoughts on this? And could you tell us a little bit about Richard and his life?

R: Right, I tend to work with older prisoners, prisoners that have been down for decades. The older you get the more vulnerable you are to health problems, medical needs. Prisons generally provide piss-poor healthcare, and sometimes they don’t provide it at all. That’s part of the work that I do now. Just like some of the things I just went over that people can do for support, well for example one my codefendants still in prison is Tom Manning, and he is now in a segregation unit in a wheelchair. So not only is he locked in his cell 23 hours a day, but he’s in a wheelchair in that cell. I’ve done an awful lot of solitary and isolation time, but I was relatively young and healthy when I did it. If you are disabled, and if you are ailing, if your health is failing, and you’re old, that presents more challenges, especially if they get you in segregation or solitary.

The reason Tom’s in a wheelchair is because of medical neglect. If he had been given the kind of medical care that should have been provided years ago, and because they didn’t provide it in a timely fashion, the price he paid for that is essentially losing the function of one of his legs, and the second leg is compromised to the extent to which he’s in a wheelchair now. And I can’t tell you how much time and effort we have put into getting an outside lawyer and an outside doctor to press the Bureau of Prisons to provide adequate medical care to Tom – I’m using him as an example – in a timely fashion to avoid the worst kind of consequences. It’s been an enormous struggle. We have to take this struggle on because it’s bad enough that we haven’t been able to get him released, it’s bad enough for him to be in a cage.

But to be disabled and not be provided medical care when you’re in pain and suffering, when the consequences could be further debilitation of your health and death, we have to do what we can to alleviate that. We’re going to see more of this with longer sentences. Most of us started our sentences fairly young. Some, like Jalil, former Panther who is still in prison after 45 years got his sentence at 19 years old. We’re still working on that, and we don’t have any money. It’s become harder over the years because we haven’t built the kind of movement that we need that will provide legal assistance when we need it without having to write our big check.

We need to have a movement that will have a medical cadre that will step up when we’re dealing with these kind of medical and health issues. Right now we have a few lawyers and medical people that will help us, but the demand is beyond what they can provide. And so Richard Williams, when he died, and he died prematurely, a contributing factor was that he did not get adequate medical care when he should’ve gotten it. He didn’t get it in a timely fashion, and when they sent him to the prison medical hospital in North Carolina it was too little, too late. He was already terminally ill essentially. And he experienced some health problems because when he was in a federal prison in Lompoc, they had locked him up in segregation.

When they put you in segregation, if you have a health problem, it will get exacerbated. You can’t sit in a cage for 23 hours a day, that won’t help when you have a heart problem which Richard did, when you’re battling cancer which Richard did. Living in that kind of extra-stressful situation within the prison, essentially you’re in a jail within the prison, that’s going to exacerbate health issues, and that’s what happened with him. And again, it took him a huge amount of time to build a campaign to eventually get him out after nearly two years in seg.

Had we had a movement that was on a firmer footing at the time, if all these individual defense committees supporting this prisoner or this small group over here, if we were all on the same page, we could’ve gotten a much quicker and more coordinated response in sharing the resources where we might’ve been able to get Richard released from seg long before he was, and get him the kind of medical help he needed long before he got it. It just so happened that I saw, last week when I was in Boston for the big welcome home for Oscar Lopez Rivera event in Boston (Oscar is the last of the Puerto Rican Independistas released from prison). Well there were these events welcoming him home in Boston. And the biggest one last week required security, and I was pleasantly surprised Richard William’s son Netdahe as part of the security detail at this event.

The apple doesn’t far fall from the tree, because Richard was a servant of the people. He was a beautiful brother who never took up more space than he needed. He was not pushy, he was not arrogant. He was a great admirer of Che Guevera, he really believed in what Che said about love being the most essential part of a revolutionary. Richard tried to live his life that way. He was not an arrogant type, a boastful type, but he was the type of person that if he said he had your back, he had your back. You could depend on him. And he wasn’t without his flaws, but those flaws never got in the way of that kind of commitment, where you know if he’s behind you, you don’t have to keep looking over your shoulder to make sure he’s there, he’s going to be there.

The most painful part of being underground for Richard was being separated from his children. His children where not underground with him, so he never saw them when he was underground. And that was added weight for him to carry. Richard was, like I said, not one to make demands, he was one to go out and punish the guilty. He had no problem taking action against corporate America and US imperialism. He was the type of person that would sit in a cell and if he was in pain, he would have to be in real serious pain before he’s going to ask people for help. That’s why when we first got word of his problems in Lompoc, it was like, Richard you have to make your issues known, and you have to advocate for yourself, because there is no movement that’s going to do it for you, so we have to go to these scattered groups to seek support. He stepped up at a point. I still miss him.

J11: Many of the long-term political prisoners in the US are in prison as a result of armed actions taking in the ‘70s and ‘80s. While many of these comrades have come up for parole, and many of them have been eligible for parole for many years, pressure campaigns from the Fraternal Order of the Police and other groups often result in the denial of parole. Of course, just recently we had the counter-example of Herman Bell being released despite the opposition of all these police groups, but that seems to be more the exception than the rule. Are there efforts you think we could undertake to fight this and continue to fight for the parole of these comrades?

R: I’m working on a parole campaign for one of the political prisoners right now, who’s coming up in October. Unfortunately, because we don’t have this massive movement, it’s his only avenue out, so we have to make the best of it. Herman Bell wasn’t released – 45 years he was in – until activists on the outside got policy changes in the New York state parole system and some changes in personnel. And that was part of a larger picture in New York where they have so many elderly prisoners doing humungously long sentences. Herman benefited from activists who saw that, at least in New York state, if you could change parole policy, get it changed a certain way, the side-effect of that would be to affect people like Herman, who’s 70 years old, and was repeatedly denied parole.

At least in this instance, it was able to parry and block the attempt by police organizations to reverse the parole board’s decision to keep Herman in. If you would have asked me this question 5 years ago, I would’ve said one of the things that’s got to be done, and I’ll say the same thing today, it’s not the only thing that has to be done, but we have to countermand the power and leverage of police organizations to run these parole boards, to have a presence on them on same cases. It might be through retired police or retired prosecutors, serving on the boards for whatever, or just through the kind of political clout that they have.

Because we’re seeing the same thing happen in a different state: Pennsylvania with the MOVE prisoners. It’s really the power of the police organizations, the same police organizations who originally opposed Mumia’s effort to get his death sentence overturned. And now they’re opposing his effort to get his life sentence overturned. Those are the same police forces in Pennsylvania that are opposing the release of MOVE prisoners. The MOVE convictions are some of the straight-up most unjust convictions thus seen among any prisoners, including political prisoners. Every time the MOVE prisoners come up for parole, it’s the same police-influenced board using the same policy to send them back to their cells with a denial. Ramona Africa was just in Maine a couple of weeks ago and speaking about this.

I don’t know all the particulars of Pennsylvania parole laws, but something along the order of what they did in New York, they might be able to do in Pennsylvania, which is actually get a policy changed, and get some of the faces on the parole board changed so that it’s not stacked with law enforcement, and they’re not doing the bidding of the police organizations. And it also helps a great deal if you have good legal representation when you’re going up for parole. I know Herman Bell’s lawyer quite well because he was the lawyer on our cases. But there are less and less lawyers that are willing to work pro-bono these days for political prisoners. It’s not like it was decades ago when it was more so-called movement lawyers who would be willing to step up.

My litmus test for a lawyer is what kind of fighter is that lawyer. Not what kind of law school credentials he or she has, but if that lawyer’s going to fight. And that fight goes long after the trial and conviction are over. Sure you want them to fight during the trial, because if you can win there you then you won’t see the inside of that cage, but if you lose there you could be in a cage for decades, for a long time, you could die there. So you want a lawyer who’s not going to forget you after you’ve been bundled off to prison. Those are the lawyers that matter the most. And a lawyer like Bob Boyle who represented Herman and worked on Mumia’s Hep C cases, continues to work with political prisoners long after their convictions. You need that kind of legal representation.

We did a fundraiser here in Maine for Herman last November. Until we build this movement that I keep referring to that we need to build, you do what you can. A small group in Maine of political activists got together and raised around $500 for Herman’s effort to get out. And I said, shit, if we can raise $500 in Maine, what about $500 in each of the other 49 states, whether it’s New York or Florida, then you’ve got $50,000, and then it matters. Because if you’re fighting for this person’s freedom and parole, there are costs associated with that. For a lawyer to go to New York City and drive five hours north upstate to visit Herman, that’s a whole day gone. It’s a whole day not making any money, it’s a whole day where you’ve got to pay all your gas and toll bills, and maybe stay at a motel overnight. We’ve got to help people do this.

J11: There are often times in campaigns for the release of long-term political prisoners where supporters use this rhetoric of “clean records” or “good behavior” while they were doing their time to argue for their release. My understanding is that you didn’t have a reputation for good behavior while you were in prison, and paid the price for that, as well as your political convictions, with doing time in the supermaxes and CMUs and spending 13 years in solitary as you mentioned. So what hope do we have for getting released our friends who can’t claim a clean record? Are there other approaches that you see some value in?

R: It’s going to vary from case to case. There are some political prisoners that have some very serious charges against them, more serious than others. Some political prisoners have much longer sentences than others. Five years is a hell of a long time to go to prison when you’re 24 years old. All of a sudden they’re taking what should be the prime of your life away from you and putting you in prison. But five years is not like a 50 year sentence. What you can do varies from situation to situation. I have seen, especially for parole, there’s an image thing involved because those who oppose your parole, those parole board members who you want to affect in a certain way, or you’re trying to do something through the media. I know that we political prisoners with the UFF have been demonized and dehumanized in the media.

I’m doing an archive at U-Mass with all the media stuff I got on UFF, it’s going into the archives so it’ll be publicly accessible. If you look at this stuff, they make us look like the most evil, violent, threatening people in the world. Your file, your paper, whatever the Bureau of Prison or prison system wherever you are, whatever media accounts they have of your case, FBI documents that are in your file and in your folder that parole board members are going to open and look at, it’s going to have a lot of negative stuff in it. Because they don’t view people like us very favorably, so there’s a battle for image going on.

I can understand people trying to get someone parole emphasize years of good behavior, saying they started this kind of class, or were mentors to some gangbangers or whatever, or showing that they were an Iraq vet or Vietnam vet. I don’t see a problem per se if that is part of the public image that you want to project to build support for this prisoner’s release. On the other hand, we need to still hang tough with those prisoners who have unfortunately have found themselves targeted and they end up with X number of disciplinary infractions because they’ve written something or published something political. We’ve seen this with a number of prisoners. They’re not going shake those disciplinary infractions when they go out.

So I think the first thing to do when trying to get someone out is to consult with that prisoner, in terms of what kind of efforts they want to see on their behalf. If you want to be successful in the way the Puerto Ricans were successful, you have to go beyond the usual list of suspects. You just can’t go to a narrow part of the left and expect that’s going to carry you, that this prisoner’s got serious convictions and doing a lot of time. That’s not enough. You’ve got to broaden that base of support, which means you may go to certain media outlets, you may go to certain religious organizations, you may go to certain professional organizations, you may go to certain politicians – local, state, county, federal – to garner that support. If you decide at the beginning that you don’t feel that you need that wide of support and that depth of support, then fine. But if you want it, you have to present yourself in a way that they can relate to.

I sorta split the difference between that and being just repeating my closing statement from the Sedition Trial. When I was trying to get paroled, I didn’t have that depth of support that the Puerto Ricans had, but I wasn’t totally isolated either. There were people that were supporting me, and were willing to work for my release. When they came, for example, for letters of support from people, I emphasized quality over quantity. I’d rather have a dozen solid than 1200 people signing electronic petition, or some kind of a form letter. And I did have a congressperson support my parole, and that was an important aspect of my strategy to get out. That congressperson is Cynthia McKinney, who was probably the most progressive congressperson in the Congress at the time that I went up for parole, and has since ran under the Green Party a couple elections ago. The parole board took notice of that, that I had Congressional support. I have a parole examiner who looked at a letter of support from a close buddy from Vietnam. That resonated with this guy who was deciding my fate at that hearing. I’ve had some long-time political activists running for my support.

It really depends on the circumstances: the time, place, and conditions. I think if you go up with an absolute no-nonsense, “I’m not compromising on anything and screw you” attitude, you might as well not go to the parole hearing. Put it this way, when you go up and try to get released on parole, it’s a battle of hearts and minds. It’s like when you’re standing in front of a jury. I had to convince a jury to acquit us in the Sedition Trial on charges that could have put us away for the rest of our lives. The reason they didn’t convict us on those charges was because I had a lengthy period of time in representing myself in which I could get the message to them, that even if you think we struck a blow against Apartheid and war criminals in Central America, you shouldn’t convict us, because these were necessary actions to expose a much higher level of criminal activity by the government and corporations. They went along with that. But you’re not going to be able to do that at a parole hearing. So it comes down to the struggle for hearts and minds.

If the battle for that ends up at a parole hearing, then you need to do what you got to do based on that. You need to develop a strategy based on, while remaining principled, tactics you use within a larger strategy, you’ve got to develop like Herman Bell did within that newer developed situation where they had a new policy and different faces on the parole board.

J11: The United Freedom Front included multiple married couples with children. A common concern for parents who decide to actively resist the state is the care for their children if they are arrested or imprisoned. Groups like the Rosenberg Fund for Children have actively taken on this form of aid and advocacy. What was your experience with this? And do you have visions for forms of solidarity with the families of political prisoners?

R: I support the Rosenberg Fund, 100%. I’ve spoken on fundraisers they’ve had. They were involved early on with providing support for our kids: we had kids with us while we were underground. It’s a non-sectarian group and I have no trouble in some of the speaking engagements I’ve been in promoting the Rosenberg Fund. The Rosenberg Fund needs financial support if it’s going to continue to do the good work that it does.

As far as having kids underground, I strongly recommend that people who want to go underground do not have children with them, or decide to have children while they’re there. I was noted underground for being able to make hard decisions in a rational way under a lot of pressure. But the decision to have kids while underground, I made that based on emotions. We did everything we could to care for our kids, we had a loving family. But kids don’t belong underground.

This is not Colombia where you’ve had a guerrilla movement going on for half a century where they actually develop an infrastructure that can care for the children of guerrillas. Or like in Vietnam with the National Liberation Front, where you could be an active guerrilla, and there was an infrastructure there that would watch out for your kids and your grandmother, so you knew if you got blown away, they were going to get cared for. No group in this country, none of the guerrilla groups, have that. It just isn’t going to happen. It could in the future. I would say yeah, if you’ve got a large unconventional warfare going on, and you’ve got an infrastructure that can provide family support and other kinds of support to those doing the fighting, then you can have kids. But in our situation, no. Where I’ve seen it in other groups that were underground, going back to the Sixties, no. It was not a good thing to do.

J11: Two of your comrades, Tom Manning as you mentioned, and Jaan Laaman, remain in prison. Could you tell us about them and how we can support them?

R: Right now I’m working on a parole campaign for Jaan Laaman. He comes up for parole later this year. There’s an ad-hoc group formed that’s working on getting his release. It’s really the only avenue out in the current time, place, and conditions. He’s got 33 years in, he’s 70 years old. So we’re putting our primary effort into that. With Tom, he’s been in seg now for 5 weeks, and we’ve got to do something about that. He’s in West Virginia, US Penitentiary. We’ve got a lawyer from the Abolition Law Center in Pittsburgh that’s contacted him, since he’s not that far from there. We’re looking into this because it’s a bad situation. We’re trying to deal with his medical issues. We have a doctor, a very progressive doctor, who’s advising us on medical issues, that has supported getting our efforts to get certain kinds of medical care for Tom when he needs it. Those are the two things that are happening right now.

We did have a successful effort last year. The Bureau of Prisons was going to send Jaan to a Communications Management Unit. This is where Daniel McGowan ended up before he got out. That would have totally screwed his parole chances, because if they feel like you need the kind of supervision and “management” they call it, that a CMU provides, they’re not going to parole you. Because you’re already showing them you’re some kind of risk, just like being in Marion and ADX. So we had to stop that, and we did. We had a lot of people writing in, we went through various media sources, including the ABC listserv, Jericho’s listserv, Freedom Radio. We got a lot of people to write in and call in to oppose this. I think it was helpful that we got some legal help. I like to cite that because it’s an example of stopping a negative thing from happening before it did. Not only would it have been bad for him to be in that situation, but it would have negatively impacted his chances for parole. So that’s a situation where a lot of people got involved and made something happen.

Six months from now we’re going to need to get a lot of people to make calls for Tom Manning, because he’s sitting in a segregation cell with a badly infected leg or something. This is a tough situation we’re dealing with. What I will say is this, anybody who wants to know more about Tom or Jaan can contact me at rayluclev at gmail dot com. I will be glad to answer any questions and give people the latest. People can write to both of these brothers, right. That’s a critical link, communication. It’s something everybody can do. Yeah, it’s not going to bring him home, writing to Tom per se is not going to get him medical care. It’s not going per se to get Jaan a parole date, but it’s a link. Some of the people that were writing me wrote some of the most beautiful letters requesting my release that I saw.

But Tom Manning, if you want to write to him go to Federal Bureau of Prisons Locator, just Google it, and you put in their prison numbers. For Tom Manning, the number is 10373-016, and Jaan Laaman is 10372-016. You just put that number into the slot, and it gives you their current addresses, rather than me giving the whole thing out here. Tom is in Hazelton, which is in West Virginia. If anyone knows a good lawyer or medical person in West Virginia, that’s who we need. Particularly a lawyer. The Pittsburgh lawyer is looking into this now. But I’ll tell you, each lawyer you get can use some help. Jaan is in the US Penitentiary in Pine Knot, Kentucky. We have a lawyer working on his parole, but that lawyer is in California and needs a local representative. So anybody that knows someone in Knoxville, Tennessee or Louisville, Kentucky that could serve as a paralegal, who doesn’t need to have any legal training per se, let us know.

J11: Thanks so much for staying with us and for sharing all of that with us, this is amazing. Do you have any final thoughts you want to share?

R: Well, I will sign off with a saying from a Salvadoran revolutionary back in the day, who when he was writing to another revolutionary in prison in Turkey, said “keep hauling up the morning.” Which is a poetic way to say keep struggling whatever your circumstances, wherever you are, whatever cage you might find yourself in, whatever corner of the state you might find yourself in. As long as you pay homage to your mother, the Earth, and that sun keeps up, then hope springs eternal.