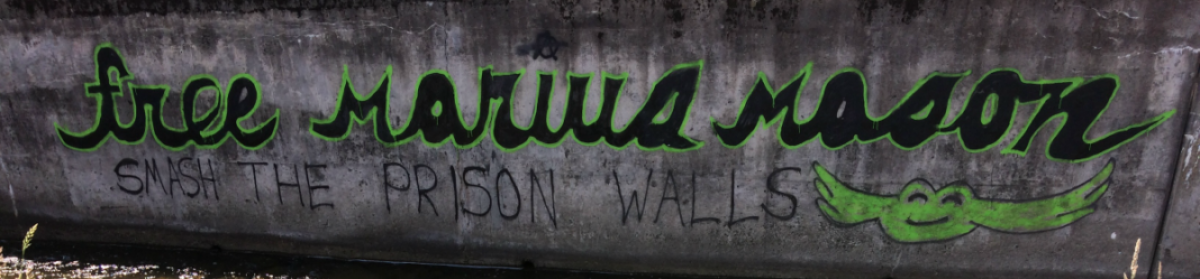

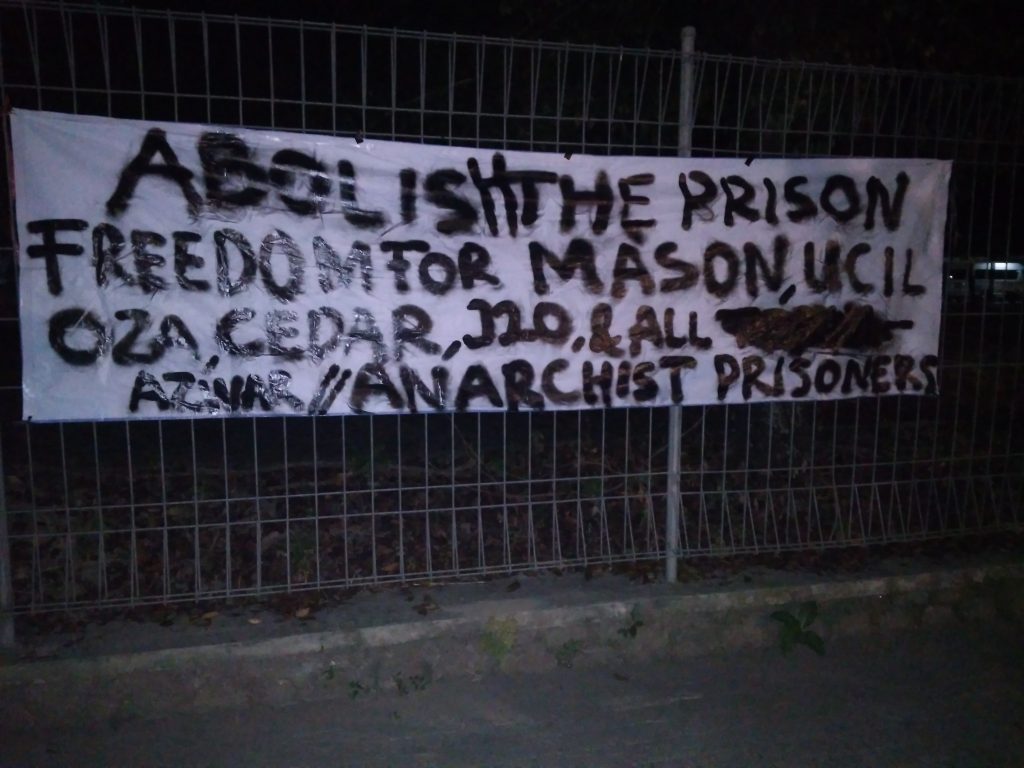

We are one week away from the June 11th International Day of Solidarity with Marius Mason & All Long-Term Anarchist Prisoners!

Events are coming in fast & there’s still time for organize events and actions in your town. Everything from writing a letter to an imprisoned anarchist to attacking the dreadful normalcy of everyday life contributes to the sort of living and active solidarity that can aid our comrades behind bars and stoke fires which may someday burn down the prisons.

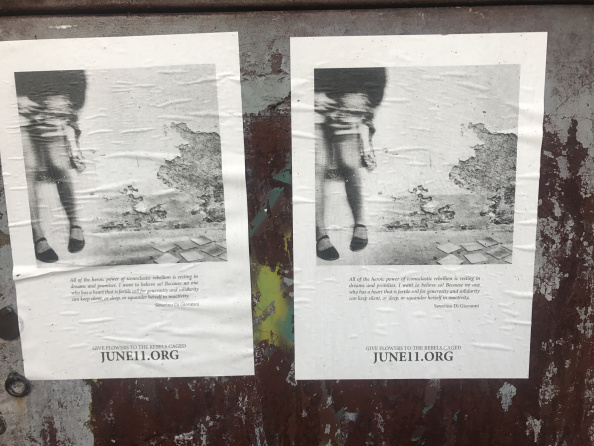

If you’re not sure what to do, check out this list of possibilities drawn from previous years, and our page full of posters, handbills, audio interviews, and more.

And if you’re looking for inspiration, a number of imprisoned anarchists have written powerful statements for this year’s June 11th.

JUNE 11th EVENTS

Please email information on additional events to june11th [at] riseup [dot] net

Asheville, NC (USA)

June 11 // 6pm

Potluck BBQ in honor of imprisoned comrades

@ Asheville Park

More info here

Austin, TX (USA)

June 11 // 7:30-9:30

The Gentleman Bank Robber movie screening + letter writing

@ Monkeywrench Books (110 E North Loop Blvd)

a benefit for Austin ABC & former-prisoner & anti-authoritarian urban guerrilla bo brown

Facebook event

Bloomington, IN (USA)

June 7 // 10pm-3am

Rock Against Racism dance party

@ The Back Door (207 S College Ave)

a benefit for June 11th organizing

Facebook event

June 12 // 7-9pm

Letter writing for imprisoned anarchists

@ Monroe County Public Library

Chico, CA (USA)

June 11 // gather at 8pm, film at 9pm

Info share, letter writing, and screening the film If a Tree Falls

@ Blackbird Books, gallery, cafe (1431 Park Ave)

Cincinnati, OH (USA)

June 11 // 6:30pm

Talks on prisoner support + letter writing

@ small grassy area across the street from Mockbee, in Brighton, between Central Pkwy & Central Ave

Then! 10pm onward…

Selling zines, books, clothing, art, etc. + free literature about June 11th

@ Mockbee 2260 Central Pkwy. Cincinnati

Contact: realicide [at] gmail [dot] com

Denver, CO (USA)

June 11 // 5:30 – 8:45 pm

Prison Abolition Potluck

Prison abolitionists will come together to break bread, learn from one

another, and network. Screening of Trouble – No Justice… Just Us, updates, prison abolition discussion and socializing.

For more info, contact denver iwoc at denver [at] incarceratedworkers.org

Durham, NC (USA)

June 17 // 6pm

Letter writing

@ The Pinhook

Grand Rapids, MI (USA)

June 11 // 7pm (tentatively)

Movies, Games, Food, and Letter Writing

@ MLK Park

Minneapolis, MN (USA)

June 10 // 6pm

Vegan potluck, letter writing, board games

Potluck & letters at 6, games at 7:30

@ 2301 Portland Ave S

More info

Montreal, QC (Canada)

June 11 // 22h

Tabling & letter writing + show

with Gazm & Cell, Wax

@Bistro de Paris

Olympia, WA (USA)

June 11 // 8pm

Benefit Show & Letter writing

with Aro, Lomes, Pines

@ 115 Legion Way SW

Olympic Peninsula (USA)

June 11 // 6-8pm

Prisoner Letter Writing & Film Screening

Letter writing & snacks at 6pm, screening of “The Gentleman Bank Robber: The Story of Butch Lesbian Freedom Fighter rita bo brown” at 7. Donations welcome and encouraged, but no one turned away! Snacks and letter writing materials/info provided.

@ Jefferson County Library (in the big meeting room) / traditional Klallam territory / Port Hadlock, WA / Olympic Peninsula

Omaha, NE (USA)

June 12

Day’s and Daze Concert

@ the Lookout Lounge (322 South 72nd. Street)

Distro table for June 11th Day of Solidarity with Anarchist Prisoners envelopes, addresses and stamps available. Stop by and write a letter to those behind prison bars.

Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

June 8-11

Fight Toxic Prisons Conference

Portland, OR (USA)

June 11 // 4pm

Letters to Prisoners

@ Social Justice Action Center (400 SE 12th Ave)

Followed by a noise demo @ 7PM

June 14 // 6-9pm

Prisoner letter writing night

@ Social Justice Action Center (400 SE 12th Ave)

Facebook event

Santiago, Chile

16 de Junio

Disidencia, accion directa y liberacion total

Conversatorios, proyecciones, musica en vivo, comida vegana, rifa a beneficio, venta de almuerzo

@ Centro Cultural Pedro Mariqueo (Pob. La Victoria)

Más información

Seattle, WA (USA)

June 10 // 6pm

Potluck, art show, benefit

173 16th ave and Spruce

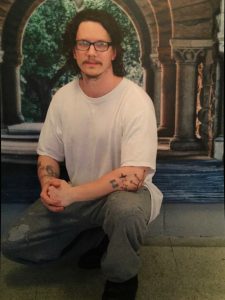

Thank you for coming together again to support all the long-term anarchist prisoners. Your support and encouragement are the life breath for anyone trying to keep heart and soul together while spending so many years away from the inspiration and motivation that our committed communities of resistance provide. It seems like the longer I am away, the more those memories seem necessary to me, feeding my spirit with the knowledge that a new world is possible.

Thank you for coming together again to support all the long-term anarchist prisoners. Your support and encouragement are the life breath for anyone trying to keep heart and soul together while spending so many years away from the inspiration and motivation that our committed communities of resistance provide. It seems like the longer I am away, the more those memories seem necessary to me, feeding my spirit with the knowledge that a new world is possible.